The Star-Spangled Banner, eh?

It might seem like a strange subject for Canadian Culture Thing but the Star-Spangled Banner has deep Canadian roots and could have never been written if not for the villain of its story – Canada.

After dishing out some payback for declaring war on Canada, by torching the White House and other government buildings in Washington, Major General Robert Ross and Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane set out to add insult to injury in the War of 1812 by going after Baltimore. Baltimore was a busy port and was thought by the British to harbour American privateers, government-sanctioned terrorists, who were raiding their ships.

The plan was for Major General Robert Ross to launch a land attack at North Point and for Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane to lay down a thrashing to Fort McHenry at Baltimore Harbour. When Ross arrived, he was greeted by 3,000 American soldiers sent to duke it out as a planned distraction while the Americans made fortifications. Ross was killed by a sniper during the battle and replaced by the less competent Colonel Arthur Brooke. The Americans retreated.

The next day, Brooke was surprised to find that he faced 12,000 troops dug in behind substantial earthworks east of the city. Under orders not to attack unless there was a high chance of success, Brooke poked around and found no discernible weaknesses in the line of defence so he sat back and waited to see the result of Cochrane’s attack of Fort McHenry.

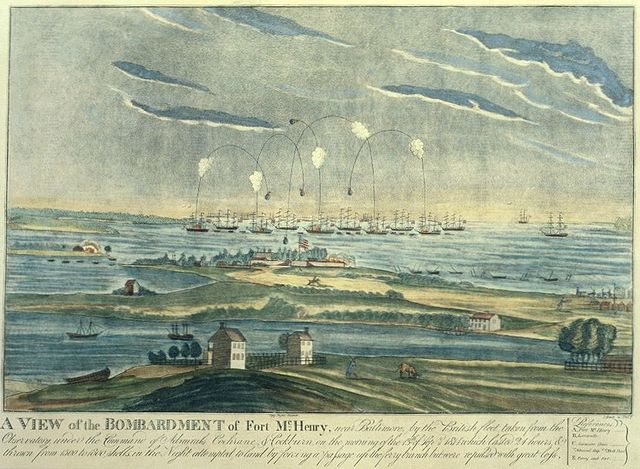

On September 13, a bombardment began on Fort McHenry. Nineteen British ships began pounding Fort McHenry with Congreve Rockets from rocket vessel HMS Erebus and mortar shells from bomb vessels Terror, Volcano, Meteor, Devastation and Aetna (the Deadpool and Rocket Robin Hood were late getting to the fight). After the initial exchange of fire, the Canadians withdrew beyond range of Fort McHenry’s cannons and continued to blast the Americans for another 27 hours.

As night fell, Cochrane sent out a landing party in small boats to the west of the fort, distracting the centrally concentrated defence for a half hour or so, affording the British a little time to blast them some more. After the 27-hour bombardment, Cochrane figured drawing the battle out might be too costly and decided to pack it in.

Brooke’s orders were clear that they weren’t to attack the American positions around Baltimore unless they were certain that there were less than 2,000 soldiers in the fort. Because of his orders and the loss of naval support, Brooke was forced to return to the fleet as they prepared to attack New Orleans.

During the assault an American lawyer (and amateur poet), Francis Scott Key was appealing to the British for the release of his friend Dr. William Beanes, a prisoner from the Washington wedgie. The British agreed to Beanes’ release but he and Francis Scott Key would have to remain on the British truce ship until the end of the siege as they had heard information that could be used against the British forces in the hands of the Americans.

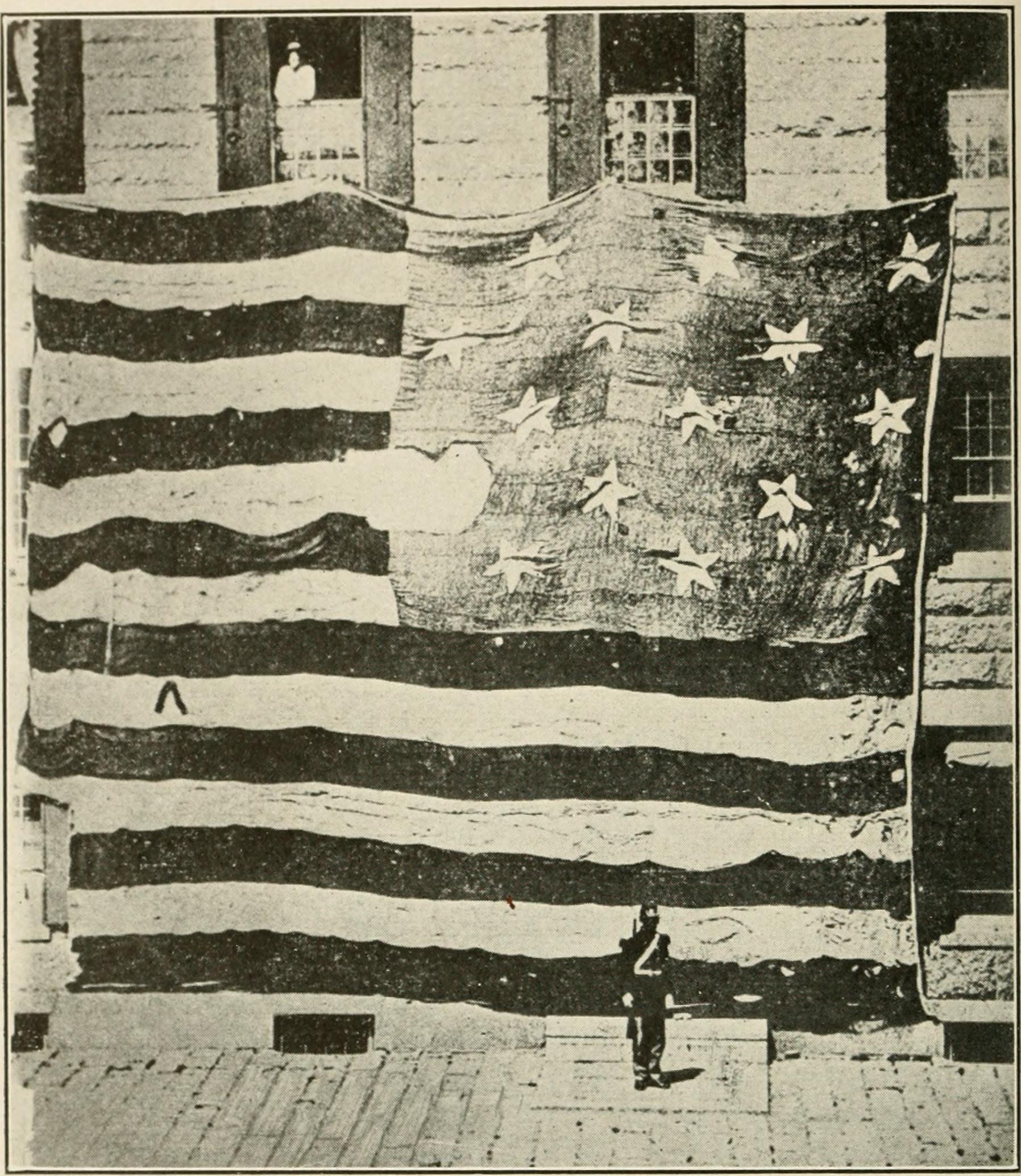

On the morning of September 14, 1814, the Americans took down the tattered and scorched storm flag at Fort McHenry and replaced it with a ginormous 9.1m x 12.8m (30’ x 42’) American Super-Flag! The flag had been made a year earlier by local flag-maker Mary Pickergill and her 13-year-old daughter. As the sun rose, Francis Scott Key could see the flag from the truce ship on the Patapsco River, some say it could even be seen from the moon. Feeling all warm and gushy inside, Key began jotting down verses on the back of a letter he was carrying and the rest is anthem-history.

Star-Spangled Banner

O! say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there;

O! say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

‘Tis the star-spangled banner, O! long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and the war’s desolation.

Blest with vict’ry and peace, may the Heav’n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: ‘In God is our trust.’

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

Some historians have mistakenly assumed that the raising of the big flag was to taunt the Canadians with a “Look! You missed this giant flag! What were you aiming at anyway?” but the Fort customarily raised this flag every morning along with reveille.

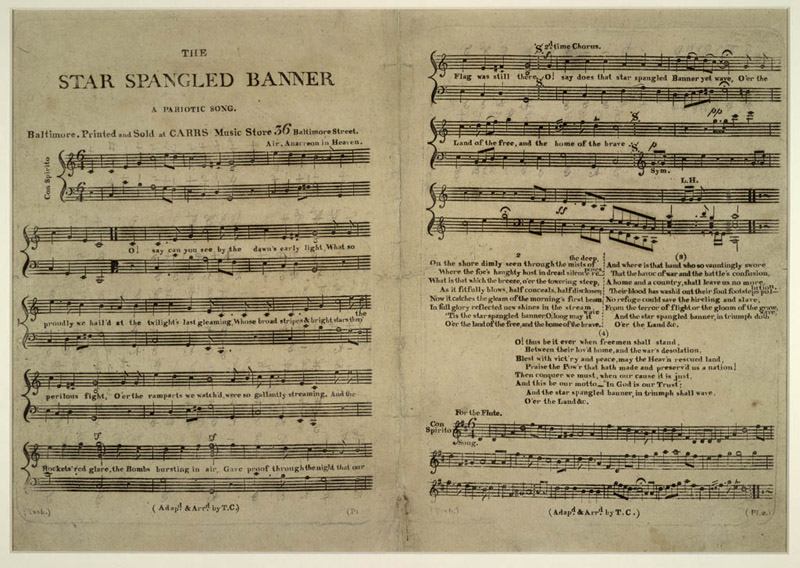

Ironically, Francis Scott Key’s poem, “the Defence of Fort McHenry” was set to the tune of a British song called “To Anacreon in Heaven” written by John Stafford Smith as the official song of the Anacreonic Society, an 18th-century gentleman’s club of amateur London musicians. Eventually becoming known as “the Star-Spangled Banner”, the American Congress made it the official national anthem of the United States in 1931.

While we all listen to this anthem at sporting events, it seems that no one knows that it was Canada’s rockets flaring red and Canada’s bombs bursting in the air. No one seems to know that the villain of the Star-Spangled Banner was in fact Canada. Though we were painted as the villain, we were merely responding offensively to a declaration of war from the United States. It’s kind of like when you come to the realisation that the poor, victimized Goldilocks has actually burglarized and vandalized the Bears’ home while they were out for a walk.

And now…

Celine Dion sings the American and Canadian national anthems prior to the start of the Montreal Expos’ home opener versus the Philadelphia Phillies on April 13, 1984. Celine was just two weeks past her sixteenth birthday. That’s right, we inspired an awesome anthem but we’ve got Celine Dion. (Sorry for the static).

Oh, by the way the Expos beat the Phillies 5-1.

Pete Rose had been having a bad year and spent most of his time sitting on the Phillies bench. He was eventually granted an unconditional release from the Phillies in late October 1983. Phillies management wanted to retain Rose for the 1984 season, but he refused to accept a more limited playing role. Months later, he signed a one-year contract with the Montreal Expos. On April 13, 1984, the 21st anniversary of his first career hit, Rose doubled off the Phillies’ Jerry Koosman for his 4,000th career hit, becoming the second player in the 4000 hit club (joining Ty Cobb).

Again, Canada seems to be the inspiration for some great American thing.