Attacking Washington during the War of 1812

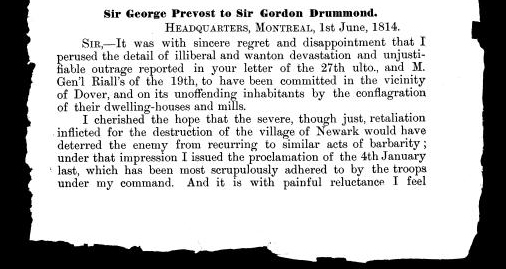

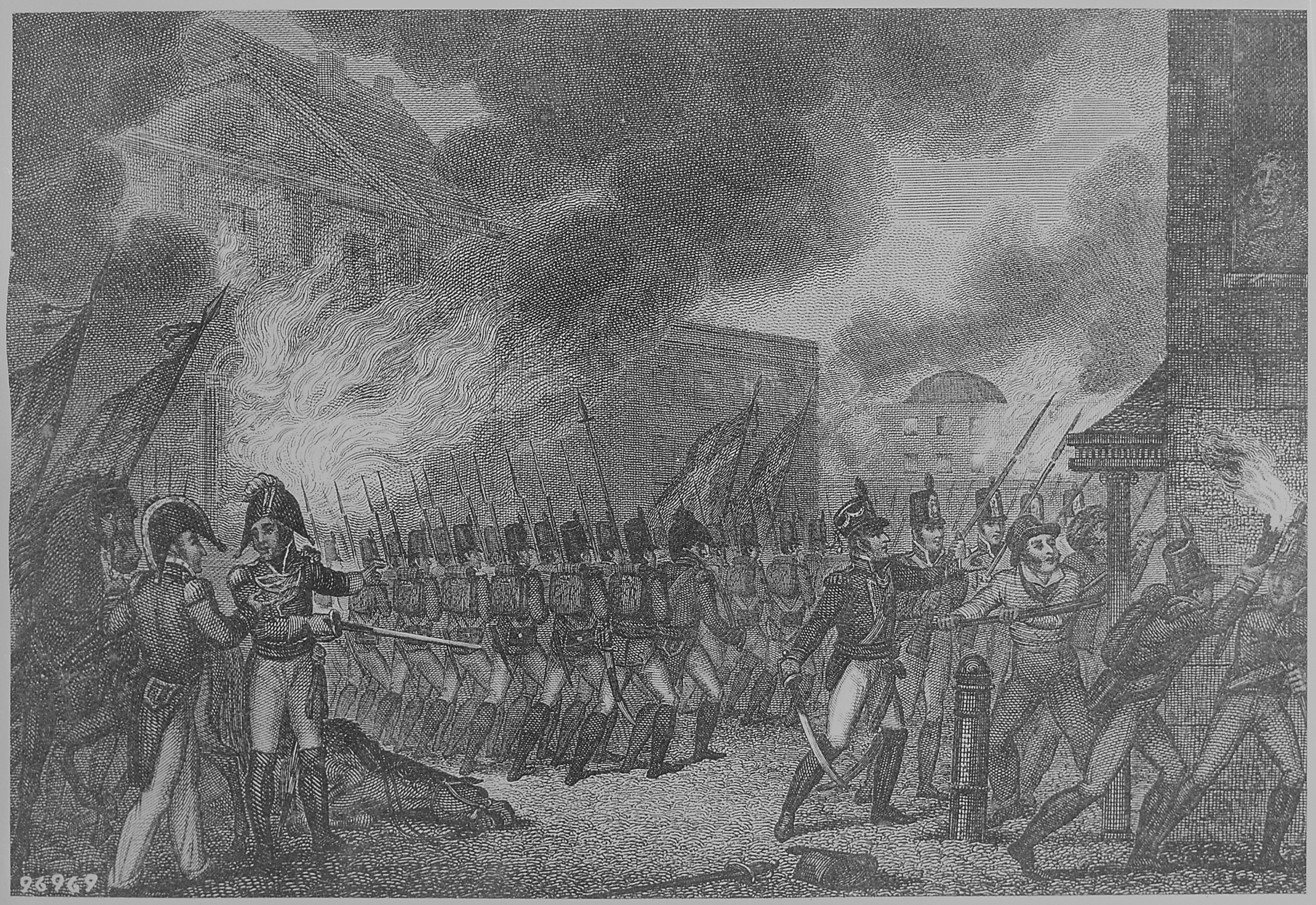

On August 25 during the third year of the War of 1812, British Troops torched the White House. They also burned the buildings housing the Senate and the House of Representatives along with some other buildings that the Americans hadn’t burned themselves. The campaign was in retaliation to lowly attacks on Canadian citizens and private property along the north shore of Lake Erie in May of 1814.

On August 24th, 1814, a British force led by Major General Robert Ross (not to be mistaken with General “Thunderbolt” Ross who spent many years hunting the Incredible Hulk although no less tenacious) occupied Washington, D.C. and set many fires on controlled targets in the American capitol. Due to the strict discipline of the British troops, private buildings and dwellings were preserved, garnering the respect of much of the American citizenry, while facilities of the U.S. Government were utterly destroyed.

Timing is sometimes everything, and in April of 1814, the Emperor Napoleon had grown tired of conquest and had decided on early retirement on the Island of Elba (even though he grew too bored to stay retired) and he allowed the British to retrieve some troops and redeploy them to the war in the Americas. That and the raised ire against the United States after unruly attacks on the north shore of Lake Erie against Canadian civilians and private property by the American war-machine, the British saw their opportunity to send a message to Washington. While Washington offered no strategic significance, its symbolic message would be heard loud and clear all over the world.

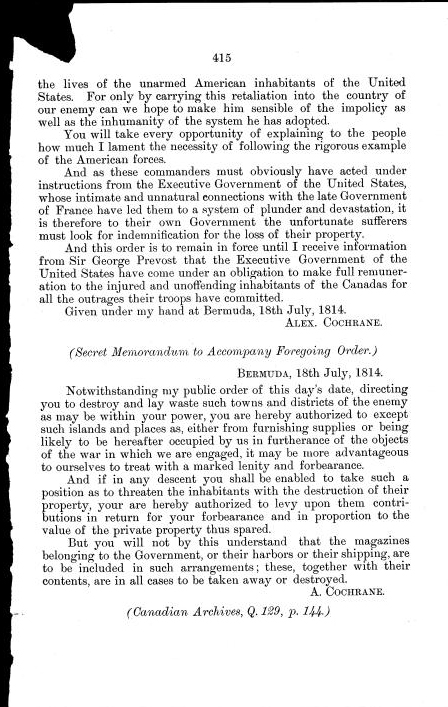

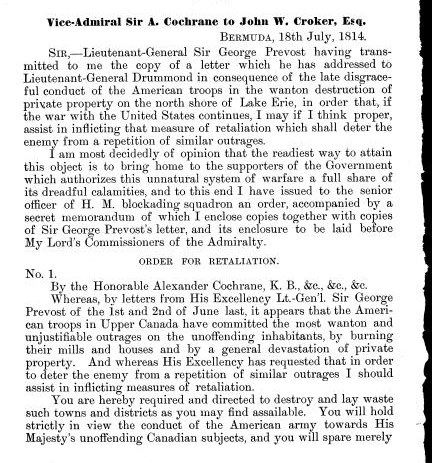

Rear Admiral George Cockburn was given his orders on July 18th to “deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages…You are hereby required and directed to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts as you find assailable. However, you will spare merely the lives of the unarmed inhabitants of the United States” (further proof that being unarmed is usually the better choice).

A force of 2,500 soldiers under Major General Robert Ross arrived in Bermuda and then sailed to the Washington area, setting ashore at Benedict, Maryland on August 19 and easily defeating a detachment of U.S. Marines and inexperienced American militia at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24th.

Immediately, Major General Ross sent soldiers under a flag of truce to agree to terms of the surrender of Washington. Though a civil occupation was attempted, the soldiers were attacked from a house full of partisans. After a quick defeat, the British soldiers burned the house and raised the Union Flag over Washington.

Next, the building that housed the Senate and the House of Representatives were torched and though the torrential rainfall from a passing hurricane preserved the buildings, the Library of Congress contained inside was destroyed.

From there the troops turned northwest up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. During the American retreat, President James Madison sought out his Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. to see what the plan was for the defence of the capital. Armstrong reported that there was none; he had expected the British to turn near Baltimore. The President, his cabinet and many other government officials fled to the mountains of Virginia. Most residents of Washington had already abandoned the city; preservation of the government’s documents and records had been largely left to clerks and slaves. While the U.S. officials fled, First Lady Dolly Madison remained to pack up the silverware and personal valuables before the arrival of the expected British before fleeing herself.

British soldiers added fuel to ensure that the White House (which for a brief time became known as the Black House until it was repainted) would continue burning throughout the rainstorm. It was said that the smoke could be seen as far away as Baltimore. Some even say from as far away as York in Upper Canada.

Continuing to retaliate, Rear Admiral George Cockburn and his troops burned the United States Treasury and intended to set afire the building of the anti-British Washington newsletter, the National Intelligencer but decided against it when a group of women persuaded him not to for fear that the fire would spread to their nearby homes. Cockburn found generosity and lit no fires. Because the paper had been printing disrespectful articles about him, referring to him as a “ruffian” Cockburn now ordered all of the contents of the building to be emptied into the streets and standing on a printing press, he announced that he would destroy all of the letter-C-type “so that the rascals can have no further means of abusing my name.” Instead of burning the building, Cockburn remained a gentleman and ordered his troops to dismantle the building brick by brick.

Less than a day after the beginning of the assault, a sudden and very heavy thunderstorm extinguished most of the fires and a passing tornado put an end to the 26-hour occupation. The British reported one soldier killed and six wounded.

The majority of Britain believed that the burnings were justified following the wonton attacks that Canada had suffered at the hands of the United States forces. Adding that the Americans had been the aggressors, having declared war and initiating aggression towards Canada. Reverend (and eventual Bishop) John Strachan, Rector of St. James Church and future founder of Trinity College, had managed to save the City of York from American soldiers intent on looting and burning it. Strachan had seen firsthand the acts of the American soldiers. He wrote to President Jefferson stating that the damage to Washington “was a small retaliation after redress had been refused for burnings and depredations, not only of public but private property, committed by them in Canada.”

On returning to our sister-country, Bermuda, the British forces arrived with four trophies from their campaign, portraits of the Mad King George III and his wife, Queen Charlotte Sophia. They were found in a warehouse on August 24 or 25, 1814 where they may have been stored since the Revolution. The spoils now hang in Bermuda’s Parliament with a pair in the House of Assembly and a pair at the Cabinet Office of the Bermuda Government.

This was the only time since the Revolutionary War that a foreign power captured and occupied the United States.